Why choose native plants?

- Kristen

- Jan 30, 2021

- 5 min read

You may have noticed lately there has been a lot of chatter in the gardening world about native plants. It feels as though all of us being stuck at home for months on end has us taking a closer look at the land we have around us and wondering how we can best manage it! We’ve had the time to notice that we don’t seem to have as many butterflies as we remember from our childhoods, and the backyard doesn’t light up with fireflies in the summer twilight like it used to. We hang birdfeeders full of seeds that seem to attract fewer and fewer species each year, and the sight of hummingbirds has become rarer than ever. It’s not hard to see that our earth’s climate change has brought about many changes that affect our land, including hotter, drier summers, extended drought conditions where years ago they would have been a short-lived occurrence. These changes are affecting everything from our food sources to our bank accounts.

This may seem like yet another doom and gloom article, but there is good news to share. It is well within our power to make incredibly valuable changes simply by choosing wisely when it comes to our landscape. This is where the buzz around native plants comes in. (Most native plant lovers are also obsessed with bees).

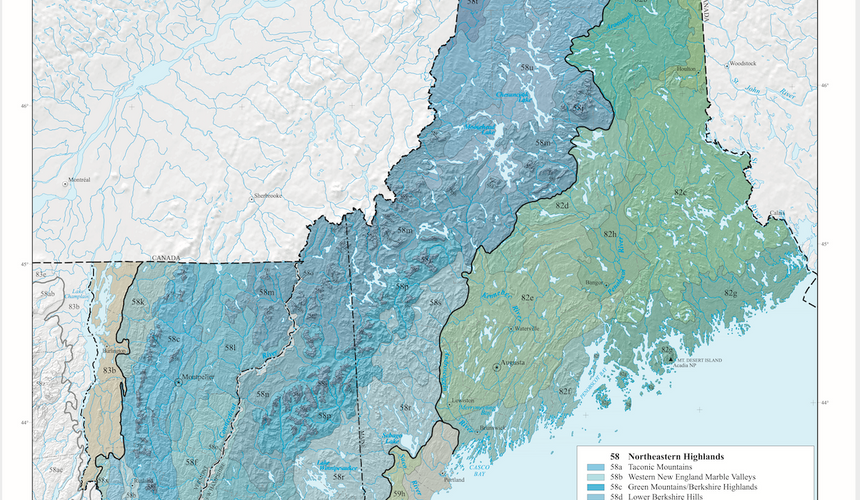

First, a touch of education. Native plants (in the US) are widely defined as those that grew in an area before European settlement. According to the USDA, a native plant is “… a part of the balance of nature that has developed over hundreds or thousands of years in a particular region or ecosystem.” (nrcs.usda.gov) Pay attention to the phrase “region or ecosystem.” We have grown accustomed to following growing zones but when it comes to natives, it is more important to understand what ecoregion you reside in. For example, in New England we have the following ecoregions:

· Northeastern Highlands

· Northeastern Coastal

· Acadian Plains and Hills

· Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens

· Eastern Great Lakes Lowlands

(If you want more in-depth information, click here for a downloadable pdf)

It is important to understand that while plants can survive in various growing zones, that doesn’t equate to them being native to a particular area. In New England, we have zones from 3 to 7, which refers more to temperature variations and hardiness than what really belongs here. When looking for plants to add to your landscape it's best to first determine your ecoregion, and then source appropriate plants as close to that region as possible.

Now that we’ve gotten the technical stuff out of the way, we can dive into the real reasons native plants are so valuable! One of the main reasons why we hammer the point of “before European settlement” is because those plants have grown in the region for millennia alongside the insects and wildlife of the same area. Native plants are well adapted to the conditions of an ecoregion, able to grow well in the soil and weather conditions of a particular area. Having evolved alongside the fauna, these plants are especially suited to provide valuable pollen, nectar, and seeds for butterflies, birds, and insects. We’ll get into the reasons why cultivated plants from outside the ecoregions cannot provide those same benefits later.

There are so many advantages to using native plants, I’m just going to list them!

· Native plants are eco-friendly and sustainable. They do not require the use of fertilizers or soil amendments, and rarely are pesticides of any kind needed. Occasionally an application of horticultural soap can help in an aphid infestation, but typically if you plant your garden with the goal of creating a well-balanced ecosystem, pest insects are often taken care of by the birds long before they become an issue.

· Plants native to a particular ecoregion are well suited to handle the water availability. In plain terms, native plants are often quite drought-tolerant, and sturdy enough to handle volatile New England weather. Natives require far less water than turf lawns, which as anyone who has experienced recent water bans can attest is a growing concern and a valuable benefit.

· Native plants provide food and shelter for wildlife. Sure, one can argue that most plants do the same, but that isn’t quite the whole story. There are thousands of insect species that specialize on a single plant for survival. Most people are familiar with the Monarch Butterfly and its requirement of milkweed species to survive. The Monarch is considered a specialist of milkweed (Asclepias sp.) as it has evolved alongside milkweed and has developed protections against the toxic sap. In fact, the Monarch invested so much of its evolutionary energy to building such protections that it was rendered incapable of surviving without it! Years ago milkweed plants were plentiful along roadsides and in meadows, and the migrating Monarchs had no shortage of food. As we humans gravitated towards wide expanses of closely mowed lawns and cleared roadsides, the milkweed plants became much harder to find, and now the Monarch is in grave danger of extinction. This same story is repeated for thousands of other insect species, most we have never heard of and will never see. Native plants provide the food source needed for these species' survival.

· Native plants fix problems. Along with being sustainable, natives are also restorative. If you have a patch of land that has been a struggle to grow plants purchased at garden centers, chances are good there are some great natives that will thrive in that spot. Natives typically have incredible root systems that work to break up compacted soil, many fix their own nitrogen from the air and add that valuable nutrient to the ground, as well as encouraging mycelium to flourish, which is a whole ‘nother topic to dive into.

· Native plants bring all the songbirds to the yard. Dr. Doug Tallamy is a well-known influence in the native plant world. His most recent book, “Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard” has been instrumental in bringing a clear understanding of the desperate need to plant more natives to the general public. If you haven’t had the opportunity to hear Dr. Tallamy speak, many of his talks can be found on YouTube, and his books are fantastic reads. I personally recommend trying out the audio versions, as you can listen along while potting up your precious seedlings. He goes into exquisite detail about how native plants support birds. To paraphrase, if you want native birds, plant native flowers!

· Native plants have immense environmental value. These plants do far more to sequester carbon from the air than the plants typically found in the average New England garden. Add to this the water-saving and the soil improvements and you will be hard-pressed to find any plant at a big box store capable of checking all of these boxes.

There is one final aspect of native plant gardens that I find is overlooked far too often, and that is the natural beauty that comes with native plant gardens. As we have become accustomed to our well-manicured (sterile) lawns and heavily mulched landscapes, we have forgotten the calm beauty of a tended wildflower meadow or the lovely winter interest of a patch of dried seed heads frequented by cold-hardy birds. Somewhere along the line, we decided that trimmed grasses are more important than the native bees that would have overwintered in the stalks, we decided that our enjoyment of double-flowered blossoms was more important than providing a food source for pollinators and that choosing an eye-catching color palette was more important than providing the colors nature intended to attract birds, bees, and other insects. By filling our gardens with the plants that found their places long before we arrived, we are being the stewards of the land as it was intended.

.png)

コメント